“I thank you Madam, for…the partial notice you are so good as to take of the part I bore in our great revolutionary struggle. I was one only of many, very many indeed who exerted their best endeavors in...the greatest event in human history, and although rivers of blood are yet to flow for the general establishment of its principles and its consequences toward the amelioration of the condition of man throughout the universe, they will be finally established.”

“I rejoice also in your avocation of the Indian rights and concur in all your sentiments in their favor. I once had hopes that the Southern tribes were nearly ripe for incorporation with us...

“I wish that was the only blot in our moral history, and that no other race had higher charges to bring against us. I am not apt to despair; yet I see not how we are to disengage ourselves from that deplorable entanglement, we have the wolf by the ears and feel the danger of either holding or letting him loose…”

Jefferson viewed slavery as immoral, wasteful and dangerous, but he feared emancipation would result in a race war. In his 1783 draft of a new Virginia constitution, he unsuccessfully called for freedom for all enslaved children born after 1800. In 1784 and again in 1800 he argued to exclude slavery from the western territories—but he didn’t defend the Northwest Ordinance prohibition on slavery and didn’t oppose the taking of slaves into Louisiana or Indiana. As President, he signed a law passed by Congress in March 1807 that put into effect on January 1, 1808, the first day allowed by the Constitution, a national prohibition against the importation of additional slaves.

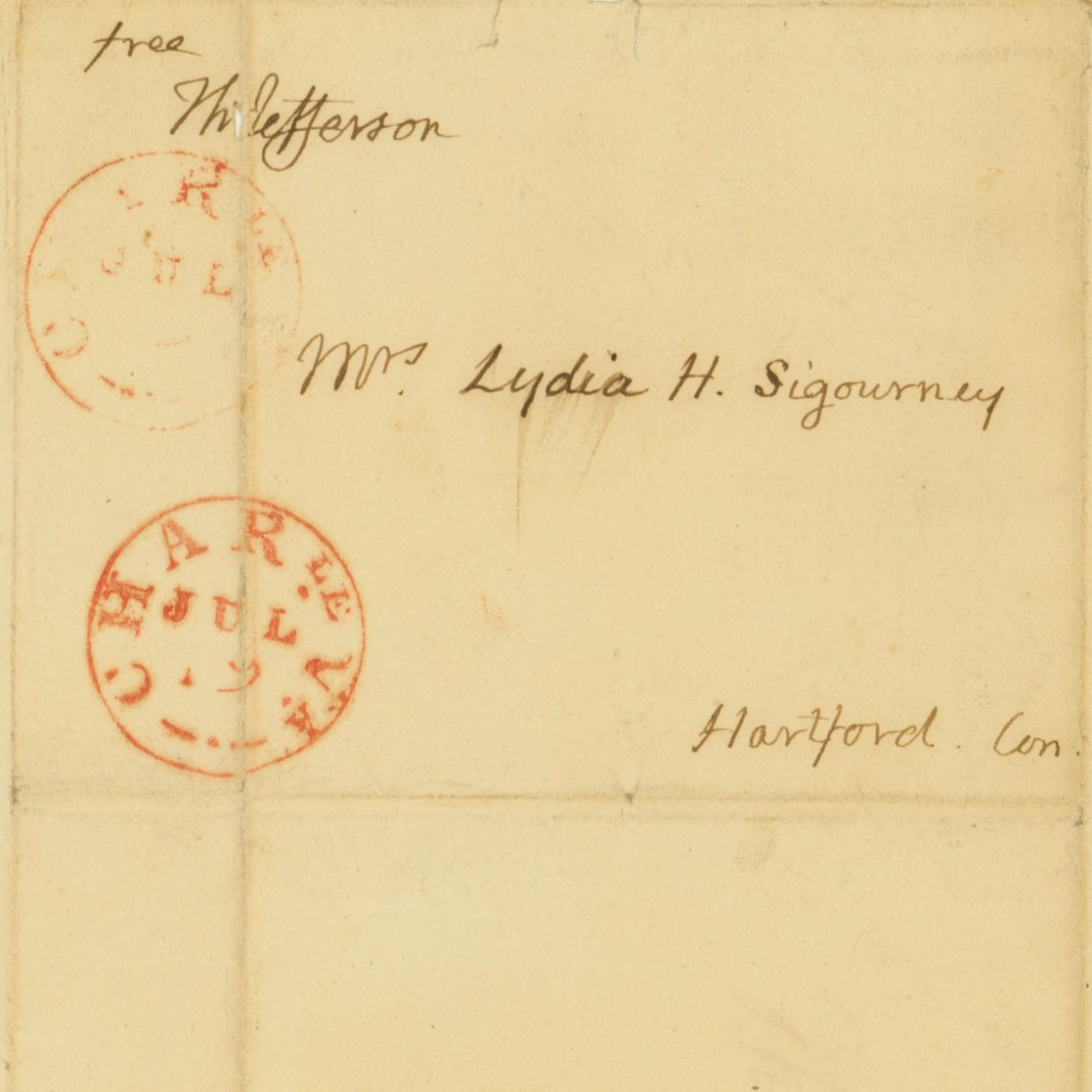

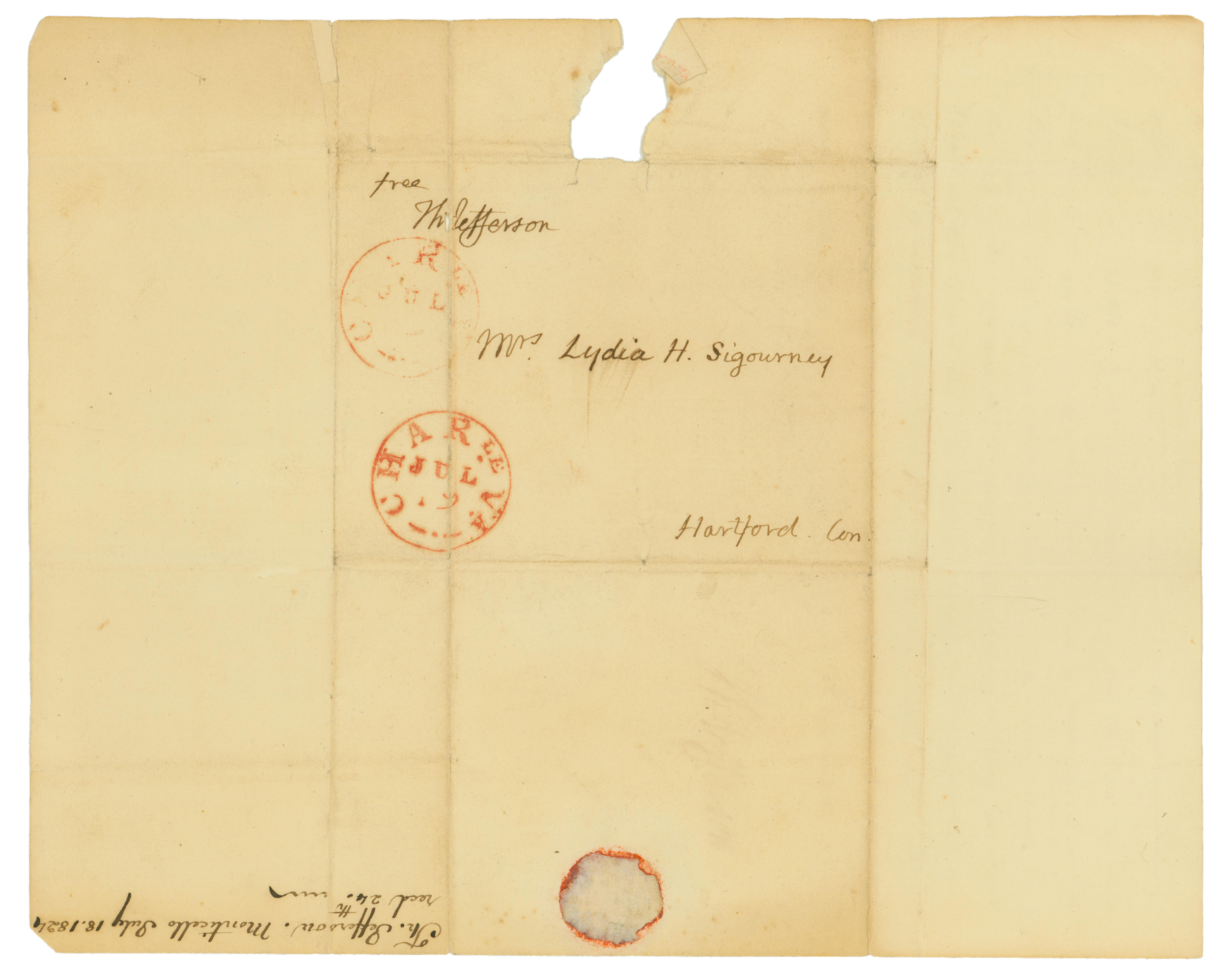

★ THOMAS JEFFERSON. Manuscript Letter Signed, text in the hand of his granddaughter Virginia, to the poet Lydia H. Sigourney, July 18, 1824, Monticello, Virginia. #21754.99