“I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are and thenceforward shall be free…”

By the summer of 1862, President Lincoln saw that tearing down the chief pillar of the Confederacy, slavery, was not just becoming possible, but necessary. He intended to issue a proclamation against slavery in June, but his cabinet advised waiting for a Union victory. The Battle of Antietam provided the opportunity for Lincoln to issue his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation which warned Southern states to abandon the war or face losing their slaves.

The Proclamation was quite risky. Racist anti-abolition sentiment was widely shared in the North and throughout the army, and the Union’s hold was still tenuous on the five slave states that had remained loyal—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia. Thus, Lincoln tailored his Proclamation as narrowly as possible to help it survive constitutional challenge in unfriendly courts. He focused on the military necessity of attacking slavery, a key resource of the Confederacy.

The most revolutionary part of the document is often overlooked: “And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages….”

Rather than hearing Lincoln patronizingly telling freed slaves to behave themselves, we read this as an announcement to whites that Black men and women who were treated as chattel now could legally act in self-defense. This is squarely in opposition to the most notorious part of the 1857 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which deluded pro-slavery forces into thinking that the slavery controversy had been solved. Chief Justice Roger Taney’s majority opinion went so far as to declare that African Americans, “regarded as beings of an inferior order,” had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Lincoln also knew that freed persons didn’t need to be told to “get a job.” He often highlighted the injustice of depriving men and women of the fruit of their own labor. These words were aimed not at the freed slaves but at those who had the power to hire them. Lincoln also declared that “such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” Ultimately, 200,000 African Americans fought for the Union, by war’s end making up ten percent of the Union army and a higher percent of the navy.

Demonstrating the evolution of his thinking, the final Proclamation eliminated his preliminary Proclamation’s references to colonization and compensation to slave owners for voluntary emancipation. Perhaps no document other than the Declaration of Independence so clearly articulated the vision of a new future for the nation.

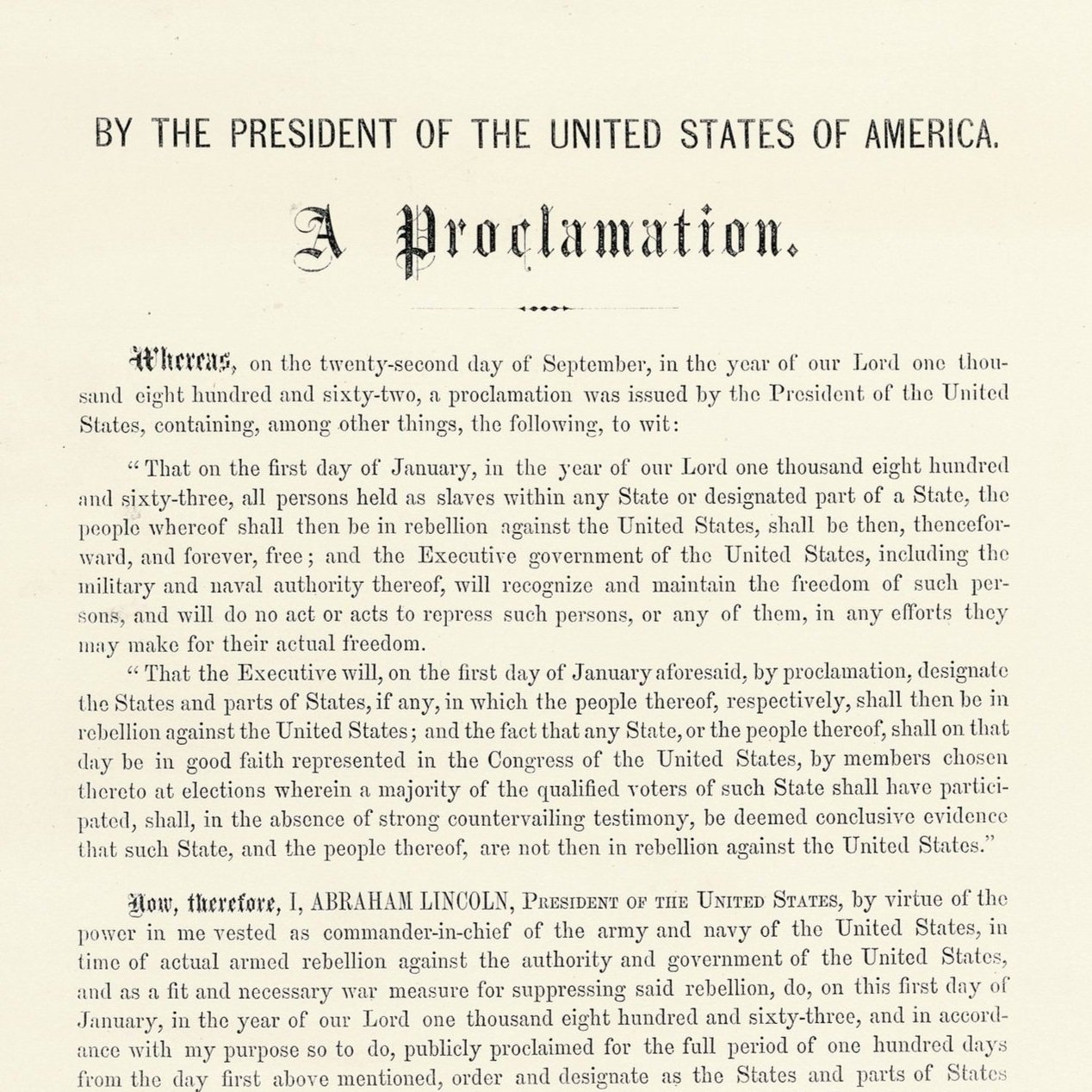

★ ABRAHAM LINCOLN. The Emancipation Proclamation. Document Signed, [June 1864], co-signed by WILLIAM SEWARD, Secretary of State, and JOHN NICOLAY, Private Secretary to the President. “Authorized Edition,” created and sold to benefit the Sanitary Commission’s work aiding soldiers and improving conditions in Union and P.O.W. army camps. #22028